Lyric Opera of Chicago – The Ring of the Nibelung - 28 March to 2 April 2005

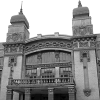

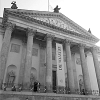

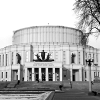

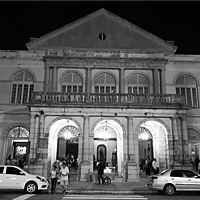

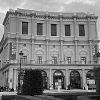

For European operagoers unfamiliar with it, the Civic Opera House, home to the Lyric Opera of Chicago, is housed in a 45-story skyscraper, which stands in the middle of the commercial district of Chicago like a gigantic throne. While on the outside quite unlike other opera houses, inside one enters an impressive lobby, a mix of Art Nouveau and Art Deco, and the one discovers the tasteful and eclectic magnificence in the overwhelming auditorium, which holds 3,563 seats.

In the 2004-05 season Chicago Lyric had its 50th anniversary and celebrated it with a revival of Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, in a production by the late August Everding, with the support of lead sponsor SBC, from the middle of the 1990s. At that time Zubin Mehta was on the podium; Sir Andrew Davis conducted the three cycles performed in March and April 2005. He has been music director and chief conductor of Chicago Lyric since 2000. And from the orchestra of Lyric Opera of Chicago, under his direction, one can hear Wagner of the highest quality in a great acoustic space. Davis is deeply impressed by the sound at Bayreuth. In the deep-lying orchestra he produced a very balanced and dynamic sound picture, in which Davis, in a manner almost like chamber music, also knew how to paint with the finest nuances. With the dynamic points, the great orchestral sections of the score and finales of the acts, he led the orchestra with captivating dramatic qualities, without ever becoming too loud, and he also always paid heed to the singers. Since the production avoided any sort of overloading on the visual or dramatic side, there was between stage and pit a great harmony and unity, so that the rendering of this complete work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk) in the best sense of the word was achieved to the maximum. The public invariably thanked Davis and his orchestra with ever increasing entrance applause from evening to evening.

Following Everding, it was stage director Herbert Kellner, himself a director at Chicago Lyric and other American opera houses, who was entrusted with the revival. John Conklin created the designs full of fantasy and was also responsible for the wonderful, tasteful costumes. Duane Schuler took charge of a lighting design that was full of ideas, subtle, and mainly symbolic, whose lighting instruments were able to insert geometric figures that intensely strengthened the plot and the musical mood of many scenes.

When this production was first staged in the 1990s, no Ring had been presented in Chicago for 64 years. With this in mind the production team and the administration of Chicago Lyric were in agreement that they wanted the first priority to be telling the story, and to abandon defined boundaries, whether political or historical. One should be grateful for the intelligent solutions of Everding, who despite great fidelity to the work brought exciting music theater with modern stylistic ideas throughout, in which every audience member could have free rein for their imagination. And it was world theater! Everding presented a fundamentally timeless but generally multicultural concept, in which clear references to Japanese Shintoism (Valhalla, the complete world of the gods) can be recognized, but also the Nibelungenlied as well as echoes of ancient Rome and Greece. The fiery red of the Shinto architecture also intensely animates the Chicago Ring in the gods’ scenes and later with the humans in Götterdämmerung (the new, false gods?). Against that, Wotan’s spear seems to be evidence of the bending bough of the World Ash Tree from the original mythology of the Ring. Outstanding is also the dramaturgical frame, within which the three Norns place the story at the beginning of all four evenings. Adding to that there darkly appears, almost as if in warning, the mask of Erda looking like an old Egyptian goddess which lends the production a point of departure.

At the same time, Everding emphasizes the humorous side of Rheingold and Siegfried. Alberich’s transformations function impressively and humorously, as with the dragon in Siegfried, a well-executed representation of the Black Prague Theater. Noteworthy were the Rhinemaidens on bungee cords in Rheingold. One could imagine oneself under water with them in a mythical blue. Often there are views of snow-covered or red-lit mountain peaks, red deserts, and a mighty planet giving associations with the endlessness, the hopelessness, the almighty power of nature and Wotan’s thoughts regarding world domination. The direction of individual characters was superlative. Thus, scenes like the reunion of Siegmund and Sieglinde, Wotan’s discussion with Fricka, and the interaction of Siegfried and Mime became high points of this Ring.

Lyric Opera offered a first-class team of singers for the three cycles. Above all, the chief god James Morris, a Wotan and Wanderer of extra class, who was honored for his 25th anniversary with Lyric after the premiere of Rheingold. His dramatic command and vocal brilliance, including a thunderous upper register, are invariably world-class, after singing this role for so many years. Jane Eaglen was Brünnhilde and is very much beloved in the USA. She presents visually and also dramatically a not exactly fleet performance of Brünnhilde if judged by European criteria, where the concept of the singing actor is more carried through. But she has a beautiful, warm, radiant middle range and also a good top that does not always seem to rise organically from the rest of her voice. John Treleaven was an outstanding Siegfried, with heroic vocal material and an unbelievable upper register. Again he surprised one not only with his high Cs in Götterdämmerung; he simply embodied the species of singing actor and showed an unusually sensitive development from inquisitive youth to a hero grown into knowledge. The intensity and humanity of his exchanges with the strong Mime of David Cangelosi belonged among the special experiences of this Ring and showed what potential lies in the often-underestimated Act One of Siegfried. Placido Domingo was Siegmund. One knows his incomparable charisma that he could still increase on this particular evening through a very emotional, tender interaction with his partner, Michelle DeYoung. Vocally he still masters this part with bravura, and is better than many younger singers in the role. But with Domingo it is the full impression that counts, and in our time this impression is incomparable. In his case, one can actually not separate acting from singing -with him in Chicago it was all one. Michelle DeYoung convinced completely as the maidenly Sieglinde, but she had slight problems with some high notes in Act Two. Clearly a better fit for her is Waltraute, which she sang marvelously. Eric Halfvarson was grandiose as Hunding, which he embodied powerfully, and as an intelligent Hagen, who never lost his ability to control the proceedings. And so he became the actual Regisseur of Götterdämmerung. His deep bass with excellent diction and phrasing called up good memories of the tradition of the famous “black” Wagner basses. Oleg Bryjak was a marvelous Alberich with a powerful, bright baritone, oppressive in his frenzy regarding the gold. Among the rest of the ensemble were some standouts: Bonaventura Bottone was a crafty tenor as Loge; Erin Wall an ideal casting as Freia, as well as Gerhilde; Jill Grove as a worthy earth-mother Erda and First Norn with a characterful contralto; Alan Held as a Gunther with a Wotan’s voice; Jennifer Wilson as a lascivious Gutrune; Raymond Aceto as a determined Fafner; and Guang Yang as Flosshilde, Second Norn, and Grimgerde. Mark Baker/Froh, James Rutherford/Donner, Dennis Petersen/Rheingold-Mime, Stacey Tappan/Forest Bird and Woglinde, handled their roles but no more than that. Less satisfactory were Andrea Silvestrelli/Fasolt and Larissa Diadkova/Fricka, who sang to some extent with unbeautiful tone, but also Lauren McNeese as Wellgunde and Rossweisse and Erin Wood as Third Norn. The octet of Valkyries only sounded good in ensemble singing.

After the gold had again – as formerly with Wieland Wagner in Stuttgart – returned to its original form, the final image of Götterdämmerung showed two children dressed in white, the color of innocence, building a small stone pyramid looking like Brünnhilde’s rock had looked previously. When they come to the last stone, the capstone, they stop and leave it aside. That is the message of this Chicago Ring: One can build anew on the foundations of this wrecked world. Wotan tried to achieve it, that is what the final apotheosis in the pit is saying, but something different is now to be made of it. A simple, strong conclusion! The faraway journey to Chicago was worth it.

Klaus Billand

Translation: R. Pines, Chicago